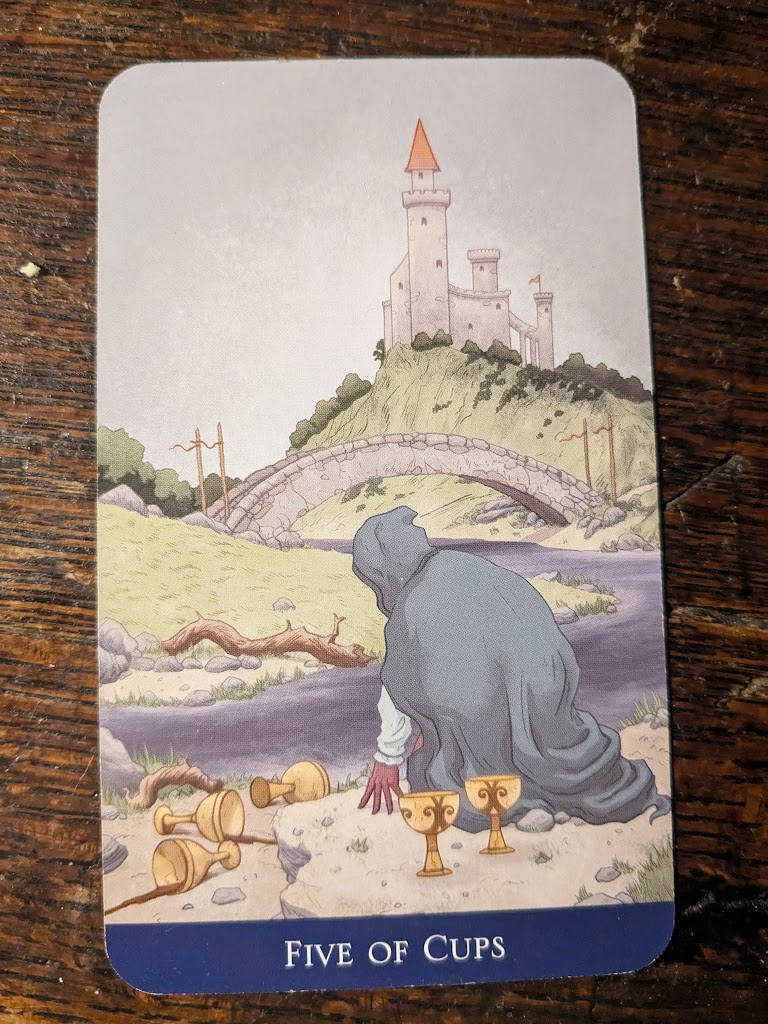

Today’s card: Five of Cups

He’s bent toward the ground, his back facing us as he looks toward the river. It’s the ground that holds him up, he almost on all fours now. His posture has more motion than yesterday’s image, the 4 of cups, where the figure sits curled in on herself. Here he has started to rise, but it takes great effort. A bridge in the background connects one side of the river with the other, as if to say there is a path across these troubled waters. There is a path back to the city, back to life with interactions and human relations. But the water is dark and torments him still.

This isn’t a crossroads. These emotions aren’t the fleeting kind, a quick bloom that vanishes. They endure like the green in a holly tree, green for a whole season. Three cups lie on their sides around him, and they’ve spilled their liquid. But two cups still stand upright—yet he’s not looking at them. He looks at the river. He’s not IN the river, but it still in a way consumes him. A subtle action writhes through the fifth card, the fifth story of cups. Fives are unstable. Something new has entered into the world to disrupt the comfort of the fours. What do you do with it?

I find a similar sense of unease in Elizabeth Bishop’s poem “Little Exercise.” She urges her reader to imagine all these scenarios that build a whole setting and atmosphere of uncertainty. A storm roams “uneasily,” the man-grove keys are “unresponsive to the lightning,” a heron makes an “uncertain comment.” And yet the sea and weeds are “relieved” to receive the renewal of rain. In the second-to-last stanza, we’re directed to imagine the storm dispersing, yet “in a series/ of small, badly lit battle-scenes,/each in ‘Another part of the field’.” This quote, as Kathryn Van Wert points out, is a reference to a stage direction in Shakespeare’s Henry VI. Van Wert says, “In the play, from the king’s perch on a hillside, the war strikes him as arbitrary and equally weighted on both sides, and before long his reverie shifts to the advantages of a shepherd’s life, whose hours are divided (like the heron’s) among eating, playing, and resting” (198). The end of the poem we’re directed to think of a man lying in a row-boat, “uninjured, barely disturbed.”

Likewise, the storm in this man’s story has passed. The series of battles are his fallen cups. The storm—his loss, his grief—are deeply present. But the two standing ones offer renewal. What does he do with this all? What does he do with the residue of the storm?

“Imagination saves the world,” says Paul Ricoeur in Lectures on Imagination. The figure is imagining what to do: He’s been disrupted. He’s witnessed, indeed participated in, an emotional battle. He has felt the “equal weight” on both sides, but he’s caught a glimpse, in a kind of reverie, of a life without this turmoil, of a “shepherd’s life”. He sees the bridge, though he knows it’ll take following the winding curve of emotions to cross it.

Bishop, Elizabeth. “Little Exercise.” Poetry Foundation. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/57048/little-exercise-56d23a2603ae7.

Ricoeur, Paul. Lectures on Imagination. Trans. Ed. George H. Taylor et al. The University of Chicago Press, 2024.

Van Wert, Kathryn. “Elizabeth Bishop and the Mechanics of Poetic Pretence.” Twentieth Century Literature, vol. 64, no. 2, 2018, pp. 191–222. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/27132295. Accessed 11 Dec. 2024.

(My Tarot deck is Llewellyn’s Classic Tarot by Barbara Moore and illustrated by Eugene Smith.)