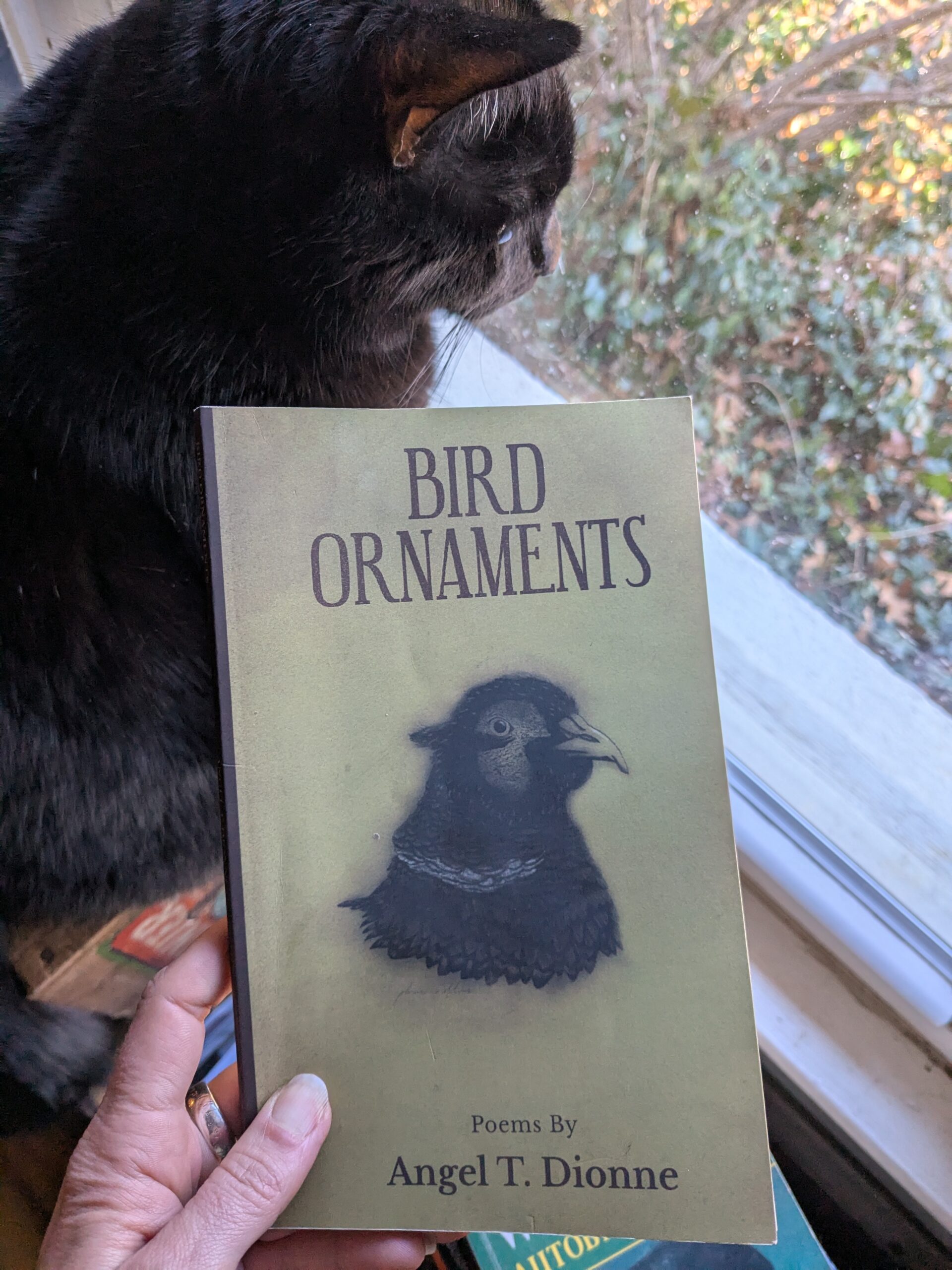

How many ways can we come to know the body through metaphor? In Angel T. Dionne’s book of poems Bird Ornaments, it can be and become so many things: a “dimensional graph/of genetic variations,” string beans for arms, caterpillars for eyebrows, teeth become adversaries. And usually when we think of metaphors, we imagine them opening up the things compared to infinite possibilities. When Juliette is the sun, she becomes the cosmos; when life is a highway we have an endless path to follow. Dionne’s metaphors work in a slightly different way, however. Metaphors are still metaphors in her poems; she creates new meanings with each of them, finds similarities among disparate things, often startlingly so. But instead of revealing the world and the body as open and limitless, her metaphors demonstrate an aspect of how we are also trapped by the images we compare ourselves to. We are trapped by our language.

When her speaker says “We are shrunken heads/and atrophied arms/dumped/in alleyways” she creates a sense in which these are cages with no door out of them (from “The Sum of What We Are”). In the next stanza, she reveals another cage: “We are elegiac carapaces,/and exoskeletons/squirming/in our rightfully assigned gutters.”

Women have long been associated with birds and Dionne follows in the ancestral traces of the etymological play between “woman” and “bird.” Not the word woman itself, but “burd” and “bird”, the former poetic Middle English for “woman, lady” and the latter being, well, bird. In medieval poetry poets played on this homophone to suggest metaphoric meaning between the two; they could mean either burd/woman or bird/bird. Dionne’s poems reveal our inheritance of this gendered limitation/endless meaning (e.g., women/birds kept in cages with ornamental value only). The poem “Bird Ornaments” itself sums up the “glass prison” we find ourselves in: “Night locks the birds in the sky,/and my bones ache/in an unreachable place.” Her speaker “marvel[s] painfully/at the beating wings/and stale talons” in the cage of night sky, as if being caged in something we belong in is something we cannot escape and something we cannot fully speak for our language limits us. Our very belonging is a cage.

Limitation of language is another kind of cage Dionne reveals in her poetry. The adjectives she uses to describe particular nouns do the work both of limiting that thing to the adjective and they act as a severance between body and body part such that her speaker is only that body part. When she speaks of “my remorseful hand” her whole being is reduced to this singular thing such that she is nothing more than this hand. And that her hand is remorseful cages the hand in its remorse such that it and we cannot see past this definition. Her poetry is a phenomenology of flat planes where the world is defined by linear mathematical equations. She reminds us how easily we slip into thinking there is no other side of a thing beyond what we see, that we can never access a whole thing; we believe in only the surface features directly before us, we become only our string bean arms, our remorseful hands.

Bird Ornaments plays with the limitations of understanding the self. Dionne’s speaker knows she’s been made into a bird, knows she’s been caged, knows that caged birds are ornaments, something to entertain, something to adorn with. But in “Mother Made Us,” the self made into ornament can be alchemized through metaphor too: “Mother made us into birds,/he admits” (italics in original). But instead of being trapped, the speaker’s brother opens his mouth, the mother walks in through his “portal” and he “spits her out,/chewed” until “Mother unravels at our feet.” Dionne demonstrates how metaphor simultaneously limits and redeems that very limitation. “My Neighbor’s Yard in Summer” likewise plays with caging/freedom when an “ornament breaks/and becomes the sun,” but beneath this very sun, a “decapitated robin” lies on the ground, suggesting “something more/than a question.”

Caging is death and is life. It is through the act of being caged itself, metaphorically and literally within the flesh and bone that is our bodies, that we find meaning in our lives. And as Dionne’s speaker reminds us, “everything/matters more than nothing…/the sea speaks/even to those/who’ve never set foot on its shores.”

You can find Angel T. Dionne’s Bird Ornaments at Barnes and Noble and Bookshop.org.