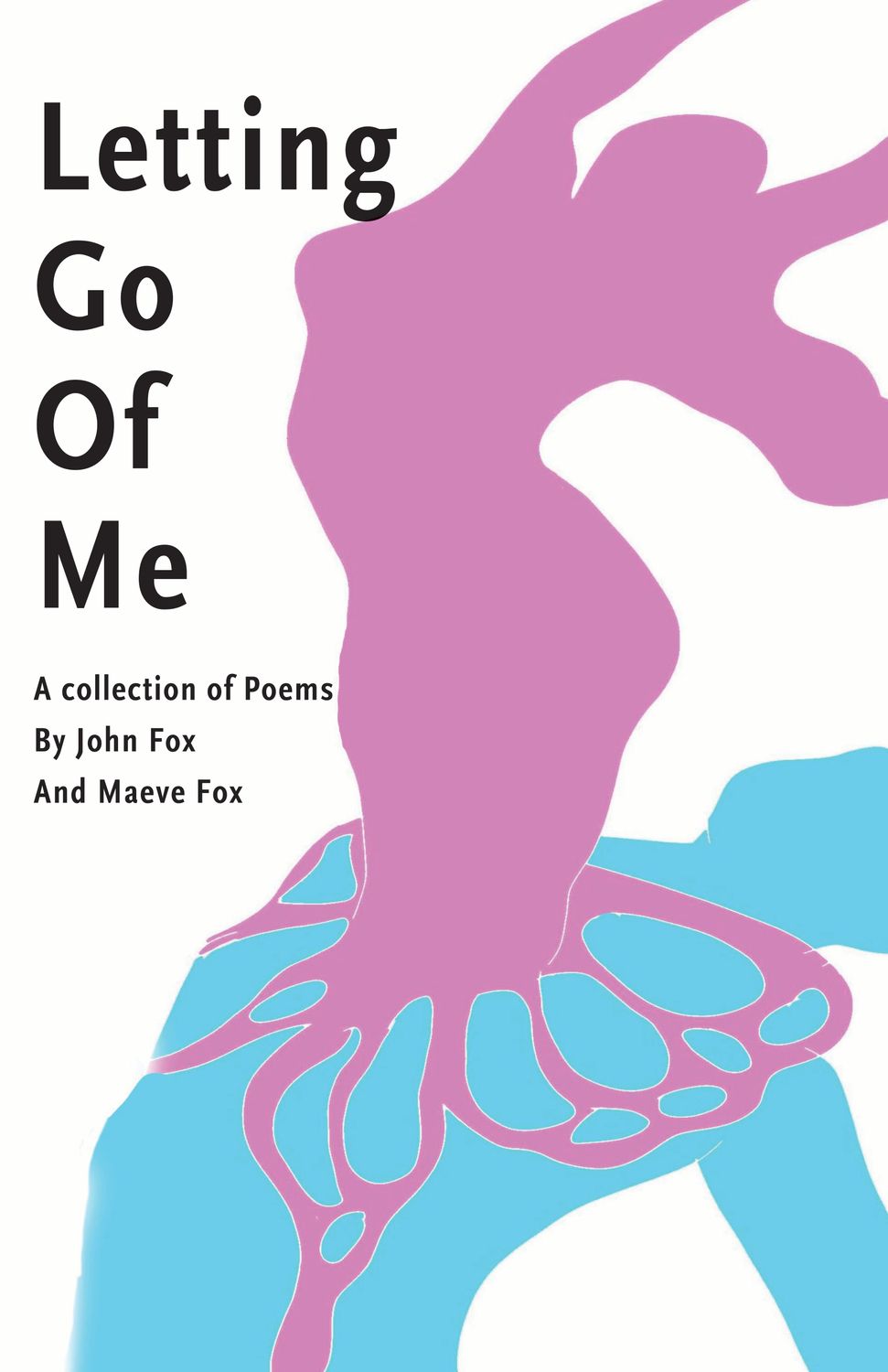

Maeve Fox’s poems show how through the act of “Letting Go,” we become. In her collection of poems Letting Go of Me, published in April 2025 by Redhawk Publications, Maeve Fox braids together past and present, and though the cover says written by both “John Fox” and “Maeve Fox,” a single voice of loving the self through many perspectives shines through.

As I began to write this review, I habitually began to refer to “Maeve Fox” as “Fox.” It’s what you do: refer to a writer by their last name once you’ve established who you’re writing about. But writing about Letting Go of Me made me pause. First I thought: I need to acknowledge it’s Maeve who put this book together, though she’s described in the introduction how John wrote some of these poems. I need to emphasize Maeve because names are important here: “My name is an ancient ritual/Bound to ancestor blood and bone” (“My Name”). Then I thought: female authors too frequently are referred to by their first names while male authors their last, some strange residue of insidious sexism. Finally, it occurred to me how it remains appropriate to refer to Maeve Fox by her last name, Fox, because Fox is, in a way, part of what tethers the “metamorphosis [she] can’t resist” from self to self. So: Fox.

Fox’s braiding of identity is what most strikes me about her collection of poems. Her poetry shows we are never just one thing, never just a single identity, and yet we are the same person now, in adulthood, as we were when children when we woke up with many siblings in a house with one bathroom to the aroma of grits slathered with butter on a slow Sunday (“Grits and Butter”). Fox’s poetry reminds us we can change and still be ourselves. That sometimes change is frightening, unsettling; but she also finds the anchors in her life and holds to them, stability within change (“Eight years old and listening/to an invisible monster try and get in/as my Pawpaw peacefully snores” from “Mountain Tales”). She shows us even when we change there is stability of the self. The self can be the anchor and we can revel in it. Sometimes, Fox shows us, while change—transformation—is often frightening, it can be the very thing that allows us to become ourselves.

One aspect of Fox’s braiding is her assembly of woman. In “Assembling a Woman Over the Years,” time is not linear, but shifts back and forth, as a braid weaves strands, assembles a pattern of life. There is “a young boy [who] holds hands/with a raven-haired boy.” Then, a man who finds a woman beneath the razor. A boy who steals clothes from the laundry, steels himself, “clumsily fastens a bra/around a flat, skinny chest.” There is a mother who sees her daughter, a woman, for the first time, peeling potatoes. Boy. Woman. Part of this assembly means living with the past, a past “you” and a present “I”: “I can’t hide or forget every little reminder/of a life you lived and I spectated./I will let you go, write you into the past/a ghost name on a book that sits on the shelf.” (“Letting Go of Me”). Fox plays with voice where she speaks strongly from a first-person I, then switches to a “you,” causing the reader to pause and ask—which “you” does she mean—thus embodying the dissonance that occurs when we don’t know from which voice we are speaking—mine? Or someone else’s?

Another kind of braid in Letting Go of Me is her braid of self with place. As Alastair McIntosh urges his readers to do in Soil and Soul, Fox begins from the ground she stands on: she is a Southern Appalachian woman with a “sixth sense honed by years/of getting caught in sudden summer showers” (“Mountain Magic”). Mountains have “enchanted our sense into weathervanes/more accurate than the man/on the news channel.” Her many metaphors are appropriate to the rural Appalachian landscape: Her “earrings hit the counter like gunshots” (“Deconstruction”); she wants “to love you like kudzu/loves an old house in a field” (“Of All the Things Before, After and In Between”); she is a “fish/struggling to swim past a large dam”; wind is “a spectral hand rattling the windows” (Mountain Tales). Her metaphors paint the landscape of the Appalachian south, even when the poems aren’t directly about place. And just as Fox shows us that she—that we—are not mono-identitied, neither are the places we call home. Through these varied landscapes of “thorns and briars,” of “creeping flowered vines,” Fox finds an anchor; she finds a self: “We are what our Momma and Mee-maws/shaped us to be” (“Southern Girls Are Made Of”).

Fox’s poems teach those who fear revealing their true selves. We fear rejection, we fear violence, we fear being hated, abused, denied. We fear ourselves. Her poems reveal suffering the consequences of toxic masculinity, how it can lead to fear of showing love to one’s own child (“My teenage son hugs me and I feel awkward/instead of embracing him properly” from “Man Card”) or how it can cause us to utterly stifle any emotions except for anger, the only appropriate male emotion (“anger is a perfect emotion/if you are holding the man card./Anger is strong, anger is powerful,/like an open hand across the face of a child”). Her poems show us the consequences of denying our emotions in a world that reveres stoicism and anger (“I’ve been an adult for longer than I was a child/and yet I’ve only cried four times/since I graduated high school”). And her poems model ways of working through these consequences.

As a woman, Fox is able to express emotion. And she feels herself. She finds harmony with herself while wearing flower patterned dresses over shaved legs (“Euphoria”). She never denies her past as a man; she had to work through it to be a woman. The delight her poems express in being oneself is infectious. The truths and vulnerabilities she writes into poems, and the regret of not having been herself sooner, all open pathways for her readers to inquire of the self: who am I, but who am I also? Fox’s poems reveal to us how past is ever braided into our present selves, but the very existence of the braid is more than the past, but always a new, changing present.

You can find Letting Go of Me for sale at Redhawk Publication’s website.