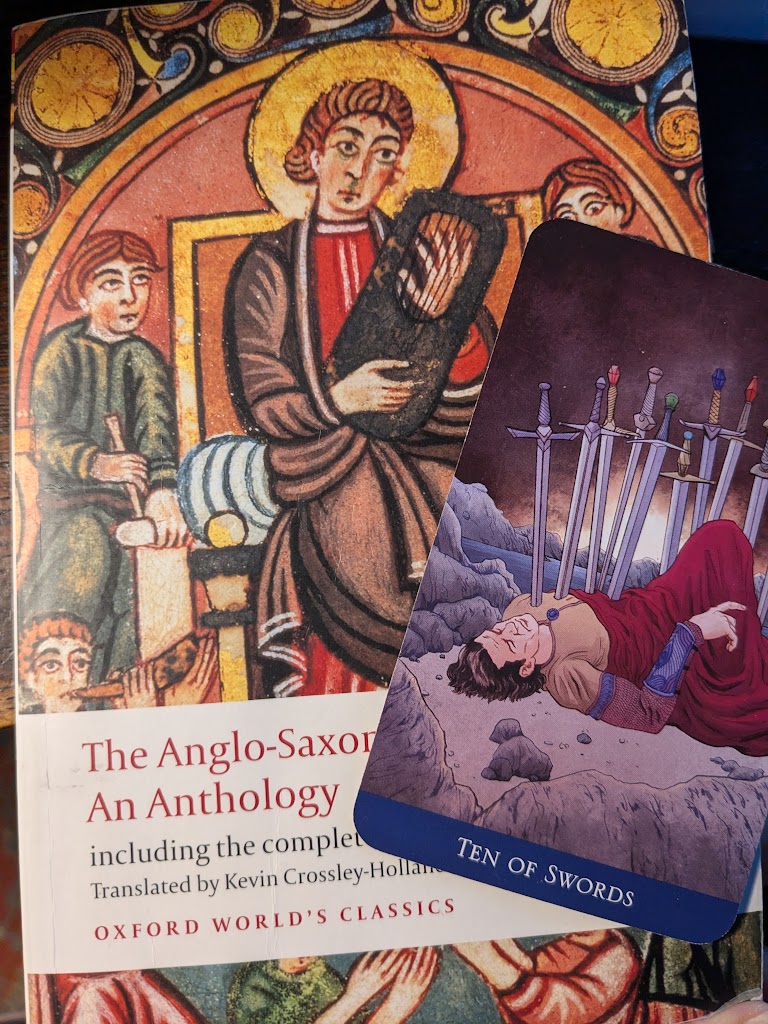

Tarot card of the day: Ten of Swords

The standard Rider-Waite deck shows a man with ten swords stuck in his back as if he were a porcupine. My deck has the cards stabbing his front. At first I was thinking that perhaps the traditional image is one of betrayal by others and mine is self-betrayal. Yet I think there’s a suggestion of both in each of them, for when someone else backstabs us and we let them, that is a betrayal of the self. So the question becomes not who is betraying us so much as how we choose to respond to betrayal in general.

I searched for other representations of the Ten of Swords on Google and found one with a woman lying on her side, holding her cell phone, the swords in her side, and below her is written “everything is fine.” Yep—sounds about right. In another image, a woman is being stabbed from the front; she is even pressing one in herself, and blood trickles from her wounds down to a red flower (this watercolor along with her other artwork is beautiful, by the way! : https://natasailincic.com/product/ten-of-swords-tarot-of-the-witchs-garden/…I’m not being paid to endorse her, I literally just found it and love it.). The woman stabbing herself offers a clear interpretation of self-slaying.

I’m reminded of the Old English poem “The Fortunes of Men.” A lovely poem, it begins by listing the many ways we can die: eaten by a wolf, starvation, in battle, by hanging where “the raven pecks out his eyes,/the dark bird rips his corpse to pieces.” (Ah! This is why I love Old English poetry.) Some will lead lives of exile who are “shunned everywhere because of his misfortune.” Of course the poem transitions into glorifying in God’s grace, but before we get there, a stanza discusses the idea of self-slaying:

The sword’s edge will shear the life of one

at the mead bench, some angry sot

soaked with wine. His words were too hasty.

One will not stay the cupbearer’s hand

and becomes befuddled; then at the feast

he cannot control his tongue with his mind

but most meanly forfeits his life;

he suffers death, severance from joys:

and men style him a self-slayer,

(Trans. Kevin Crossley-Holland.)

The imagery can’t be better: the “sword’s edge” of overconsumption. While this stanza specifically refers to overconsumption of alcohol such that we cannot control ourselves, anything overdone can lead to a kind of self-slaying, even if it’s a good thing (too many carrots?). How are we slaying ourselves? How are we letting ourselves be slayed by others? Brought to ruin? Letting the ravens pluck out our eyes, the wolves devour our flesh?

The peoples who spoke the various dialects of Old English had a deep tradition of fate. Their word for it was wyrd, and though most if not all of what we read from them is post-Christian conversion, the Germanic perspective of fate remained ingrained in their world views. (Wyrd could be likened to the Old Norse Norns and the World Tree, Yggdrasil). The poem “The Fortunes of Men” continues by describing how humans are given a fate by God, “for one happiness, hardship for another.” The poet goes on to list the sundry ways we can be fated good in our lives.

While I’m not interested in debating fatalism—I can never make up my mind; is that because I’m fated not to or because I lack conviction?—my Tarot card image suggests our hero could decide–or be fated– one way our another. The sky in the background is stormy dark. Apocalyptic dark. But on the horizon shines a burst of brilliant light. Which way will the light and the dark go? Which is coming and which is going?

One of my favorite stanzas in this poem is the one for the scop:

One will settle beside his harp

at his lord’s feet, be handed treasures,

and always quickly pluck the strings

with a plectrum—with that hard, hopping thing

Rather than finding the answer, I’ll simply continue to listen to the scop—the bard, the poet—and let mystery be a mystery.